Minutemen were members of the organized New England colonial militia companies trained in weaponry, tactics, and military strategies during the American Revolutionary War. They were known for being ready at a minute’s notice, hence the name. Minutemen provided a highly mobile, rapidly deployed force that enabled the colonies to respond immediately to military threats. They were an evolution from the prior colonial rapid-response units.

The minutemen were among the first to fight in the American Revolution. Their teams constituted about a quarter of the entire militia. They were generally younger, more mobile, and provided with weapons and arms by the local governments. They were still part of the overall militia regimental organizations in the New England Colonies.

In the Massachusetts Bay Colony, all able-bodied men between the ages of 16 and 60 were required to participate in their local militia company. As early as 1645 in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, some men were selected from the general ranks of “town-based training bands” to be ready for rapid deployment. Men so selected were designated as minutemen. Their companies were organized by town, so it was very common for their counterpart militia company to contain relatives and friends. Some towns in Massachusetts had a long history of designating a portion of their militia as minutemen, with “minute companies” constituting special units within the militia system whose members underwent additional training and held themselves ready to respond at a minute’s notice to emergencies, which gave rise to their name as Minutemen.

Members of the minutemen, in contrast to the regular militia, were no more than 30 years old, and were chosen for their enthusiasm, political reliability, and strength. They were the first armed militia to arrive at or await a battle. Officers were elected by popular vote, as in the rest of the militia, and each unit drafted a formal written covenant to be signed upon enlistment.

The militia in the New England colonies were organized in regiments by county. The militia and minutemen companies still were organized by town and trained typically as an entire unit in each town two to four times a year with the Minutemen receiving extra training. From the end of the French and Indian War, this was normal during peacetime but, in the 1770s, as friction with The Crown increased and the possibility of war became apparent, the militia trained three to four times a week.

In response to these tensions, the Massachusetts Provincial legislators found that the colony’s militia resources were too short just before the American Revolutionary War, on October 26, 1774, after observing the British military buildup. They found that, “including the sick and absent, it amounted to about 17,000 men, far short of the number wanted, So the council recommended an immediate application to the New England governments to make up the deficiency, resolving to re-organize and increase the size of the militia:

The Massachusetts General Assembly was stymied by Governor Hutchinson from passing a bill. As a result, resisting legislators, including Samuel Adams being among the leaders, set up Committees of Correspondence in parallel with their fellow Patriots in Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island that recommended that the militia increase in size and reorganize and form special companies of minutemen, who should be equipped and prepared to march at the shortest notice. These minutemen were to comprise one-quarter of the whole militia, to be enlisted under the direction of the field-officers, and divide into companies, consisting of at least 50 men each. The privates were to choose their captains and subalterns, and these officers were to form the companies into battalions, and chose the field-officers to command the same. Hence the minute-men became a body distinct from the rest of the militia, and, by being more devoted to military exercises, they acquired better skill in the use of arms.

The need for efficient minuteman companies was illustrated by the Powder Alarm of 1774. Militia companies were called out to engage British troops, who had been sent to capture ammunition stores. By the time the militia was ready, the British regulars had already captured the arms at Cambridge and Charlestown and had returned to Boston.

The new reorganization provided six regiments of militia with a nominal strength of 9,000 men with minuteman companies being formed from the younger, more physically fit men. The militia in New England was still midway through the process of splitting the Minutemen companies from the regular militia companies into their own regiments by the spring of 1775. For example, the old 2nd Middlesex Regiment of Foot, a provincial unit that had seen action in the French and Indian Wars, divided into a militia regiment under Colonel David Green and a Minuteman regiment under Colonel Ebenezer Bridge. Colonel William Prescott’s Middlesex regiment had not yet split and had ten companies of militia and seven of minutemen. Worcester County had managed to already complete the organization and staffing of three Minuteman regiments by April 1775.

In May 1653, the Council of Massachusetts said that an eighth of the militia should be ready to march within one day to anywhere in the colony. Eighty militiamen marched on the Narragansett tribe in Massachusetts, though no fighting took place. Since the colonies were expanding, the Narragansetts got desperate and began raiding the colonists again. The militia chased the Indians, caught their chief, and got him to sign an agreement to end fighting.

In 1672, the Massachusetts Council formed a military committee to control the militia in each town. In 1675, the military committee raised an expedition to fight the raiding Wampanoag tribe. A muster call was sent out and four days later, after harsh skirmishes with the Wampanoags, three companies arrived to help the locals. The expedition took heavy losses: two towns were raided, and one 80-man company was killed entirely, including their commander. That winter, a thousand militiamen pushed out the Wampanoags.

In response to the success of the Wampanoags, in the spring of 1676 an alarm system of riders and signals was formed in which each town was required to participate.

The Second Indian War broke out in 1689, and militiamen throughout the Thirteen Colonies began to muster in preparation for the fighting. In 1690, Colonel William Phips led 600 men to push back the French. Two years later he became governor of Massachusetts. When the French and Indians raided Massachusetts in 1702, Governor Phips created a bounty which paid 10 shillings each for the scalps of Indians. In 1703, snowshoes were issued to militiamen and bounty hunters to make winter raids on the Indians more effective. The minuteman concept was advanced by the snow shoe men.

American Revolutionary War

The British practiced formations with their weapons, focusing on marching formations on the battlefield. The military ammunition of the time was made for fast reloading and more than a dozen consecutive shots without cleaning. Accuracy of the British musket was sacrificed for speed and repetitive loading.

The militia prepared with elaborate plans to alarm and respond to movements by the king’s forces out of Boston. The frequent mustering of the minute companies also built unit cohesion and familiarity with live firing, which increased the minute companies’ effectiveness. The royal authorities inadvertently gave the new Minuteman mobilization plans validation by several “show the flag” demonstrations by General Gage through 1774.

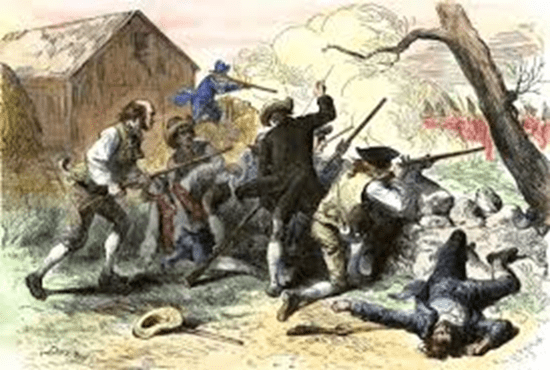

The royal authorities in Boston had seen these increasing numbers of militia appearing and thought that the militia would not interfere if they sent a sizable force to Concord to seize munitions and stores there (which they considered the King’s property, since it was paid for to defend the colonies from the American Indian threat). The British officers were proven wrong. Shooting erupted at Lexington. There is still a debate as to whether it was a colonist or a British soldier who fired the first shot. The militia left the area, and the British moved on. The British then moved to Concord and faced a larger number of militia men. However, the British were rapidly outnumbered at Concord, with the arrival of the slower moving militia; they had not counted on a long fight, and so had not brought additional ammunition beyond the standard issue in the soldiers’ cartridge boxes. This then forced a strategic British defeat on Colonel Smith, forcing him back to Boston.

A “running fight” began during the retreat. Militiamen knew the local countryside and were familiar with “skulking” or “Indian warfare”. They used trees and other obstacles to cover themselves from British gunfire and pursuit by British soldiers, while the militia were firing and moving. This kept the British under sporadic fire, and caused them to exhaust their limited ammunition. Only the timely arrival of a relief column under British Lord Percy prevented the annihilation or surrender of the original road column.

While a lot of Colonial militia units did not receive either arms or uniforms and were required to equip themselves. Many simply wore their own farmers’ or workmen’s clothes and, in some cases, they wore cloth hunting frocks. Many farmers who owned separate guns such as fowling pieces, and sometimes rifles (though rarer in southern New England) would use them instead of the militia muskets. These pieces gradually appeared in quantity, but neither fowling pieces nor rifles had bayonets such as the British used.

Minutemen tended to get more training in line tactics and drill than the regular militia. Many Minutemen company commanders put their men through more training separate from the rest of the militia. Some also expended time, money, and effort to make sure their Minutemen were well-armed. For example, Captain Isaac Davis who was a gunsmith in his civilian occupation built a firing range on his farm to train his men in firing and drill. He also made sure that every man in his company had a good musket, cartridge box, canteen, and bayonet. This was one of the reasons that his company was in the lead of Colonel Barrett’s Middlesex Minutemen regiment as the Rebels marched down to face the regulars at the Old North Bridge at the Battle of Concord.

Their American experience suited irregular warfare. In the colonial agrarian society, many were familiar with hunting. The Indian Wars, and especially the recent French and Indian War, had given colonials valuable experience in irregular warfare and skirmishing, while British line companies tended to stick to European style fighting. The long rifle was also well suited to this role. The rifling (grooves inside the barrel) gave it a much greater range than the smoothbore musket of the British, although it took much longer to load. When performing as skirmishers, the militia could fire and fall back behind cover or behind other troops, before the British could get into range. The wilderness terrain that lay just beyond many colonial towns favored this style of combat and was very familiar to the local militia.

Through the remainder of the American Revolution, militias moved to adopting the minuteman model for rapid mobilization. With this rapid mustering of forces, the militia proved its value by augmenting the Continental Army, occasionally leading to instances of numerical superiority. This was seen at the Battles of Hubbardton and Bennington in the north and at Camden and Cowpens in the south. Cowpens is notable in that Daniel Morgan used the militia’s strengths and weaknesses skillfully to attain the double-envelopment of the famous Tarleton‘s forces.

There was a shortage of ammunition and supplies, and what they had were constantly being seized by British patrols. As a precaution, these items were often hidden or left behind by minutemen in fields or wooded areas. Other popular concealment methods were to hide items underneath floorboards in houses and barns.

And so, with the help of the Minutemen, General Wahington defeated the European British army and the country of America prevailed and has prospered greatly.

The U.S. Air Force named the LGM-30 Intercontinental Ballistic Missile the “Minuteman”, which was designed for rapid deployment in the event of a nuclear attack. The “Minuteman III” LGM-30G remains in service.

The U.S. Navy VR-55 Fleet Logistic Support Squadron is named “Minutemen” to highlight the rapid deployment and mobility nature of their mission.

Recently President Donald Trump pledged his support for the Texas Minutemen Militia to arm themselves and march to intercept the migrant caravans at the Texas border to aid the U.S soldiers sent to intercept the Migrant caravans heading up through Central America to invade the United States.

Ron