(How we measure time has an interesting history. Here I have recorded for you the history of how we now measure time across the world. Do study it so that you will always know how we got here:)

Prior to the invention of clocks, watches and digital devices, people all over the world looked to the position of the sun, moon and stars as a kind of clock in the sky. Ancient peoples, for millennia, based their calendars on the position of the moon, whose lunar cycles incrementally shifted throughout the seasons, serving as an enormous generational calendar.

Remnants of March being the first month of the year can be seen in the old Roman Latin names of months: September, October, November, and December: “Sept” is Latin for seven; “Oct” is Latin for eight (ie. octagon=eight sided); “Nov” is Latin for nine; and “Dec” is Latin for ten (ie. decimal=divisible by ten).

As the Roman Empire expanded and conquered more nations, these lunar calendars were difficult to reconcile with each other. In 45 BC, Roman Emperor Julius Caesar became, in a sense, the first globalist. He wanted a unified calendar for the entire Roman Empire.

Caesar made January 1st the beginning of the year, leading some Christian leaders to consider it a pagan date. Julius Caesar introduced the solar-based “Julian Calendar,” with 365 days, and an extra “leap day” at the end of February every 4th year. Rome’s old fifth month, Quintilis, was renamed after Julius Caesar, being called “July.” As it only had 30 days, Caesar took a day from the old end of the year, February, and added it to July, giving the month 31 days.

The next emperor, Augustus Caesar, renamed the old sixth month, Sextilis, after himself, calling it “August.” He also took a day from the old end of the year, February, and added it to August, giving that month 31 days, and leaving February with only 28 days.

Augustus Caesar also wanted a world-wide tracking system to monitor and tax everyone under his control — an empire-wide census. Luke 21:1-3 “And it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed. (And this taxing was first made when Cyrenius was governor of Syria.) And all went to be taxed, everyone into his own city.”

For the first three centuries of Christianity, followers of Christ were persecuted throughout the Roman Empire in ten major persecutions.

Finally, Emperor Constantine ended the persecutions in 313 AD, and effectively made Christianity the recognized religion of the Empire.

Just as Julius Caesar unified the Roman Empire with the Julian Calendar, Constantine proposed at the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD to to use the calendar to help unify the “Christian” Roman Empire.

The most important events in the Christian calendar were Christ’s Death, Burial and Resurrection. Christ’s crucifixion as the Passover Lamb occurred on the Jewish Feast of Passover; His being in the grave occurred on the Feast of Unleavened Bread; and His Resurrection occurred on the Feast of First Fruits, or as it was later called, Easter.

The Apostle Paul wrote in First Corinthians 5:7-8 “For even Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us. Therefore let us keep the feast, not with old leaven, neither with the leaven of malice and wickedness; but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth.”

First Corinthians 15:20 “But now is Christ risen from the dead, and become the first fruits of them that slept.”

Constantine wanted a common date to celebrate Easter, and insisted the date be on a Sunday in the Roman solar calendar. This effectively ended the original method of determining the date, which was by asking Jewish rabbis each year when the Passover Feast was to be observed based on the Hebrew lunar calendar – traditionally beginning the evening of 14th day of Nissan. Constantine’s act was a defining moment in the split between what had been a predominately Jewish Christian Church — as Jesus and his disciples were Jewish — and the emerging Gentile Christian Church.

The new method of determining the date of Easter was the first Sunday after the first paschal full moon falling on or after the Spring Equinox. Tables were compiled with the future dates of Easter, but over time a slight discrepancy became evident. “Equinox” is a solar calendar term: “equi” = “equal” and “nox” = “night.” Thus “equinox” is when the daytime and nighttime are of equal duration. It occurs once in the Spring around March 20 and once in the Autumn around September 22. In the year 325 AD, Easter was on March 21.

During the Middle Ages, France celebrated its New Year Day on Easter. Other countries began their New Year on Christmas, December 25, and still others on Annunciation Day, March 25.

By 1582, it became clear that the Julian Calendar was slightly inaccurate, by about 11 minutes per year, resulting in the compiled tables having the date of Easter ten days ahead of the Spring Equinox, and even further from its origins in the Jewish Passover.

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII decided to revise the calendar by eliminating ten days. He set a leap year every 4th year with a minor adjustment. There is NO leap year in years divisible by 100, but not by 400. Thus, there is NO leap days in 1700, 1800, 1900, 2100. Yet there ARE leap days in the years 1600, 2000, 2400. It sounds complicated, but it is so accurate that the Gregorian Calendar is the most internationally used calendar today.

Pope Gregory’s “Gregorian Calendar” also returned the beginning of the new year BACK to Julius Caesar’s January 1st date. As England was an Anglican Protestant country, it reluctantly postponed adopting the more accurate Catholic Gregorian Calendar. Most of Protestant Europe did not adopt the Gregorian Calendar for nearly two centuries. This gave rise to some interesting record keeping. For example: ships would leave Protestant England on one date according to the Julian Calendar, called “Old Style” and arrive in Catholic Europe at an earlier date, as much of Europe was using the Gregorian Calendar, called “New Style.”

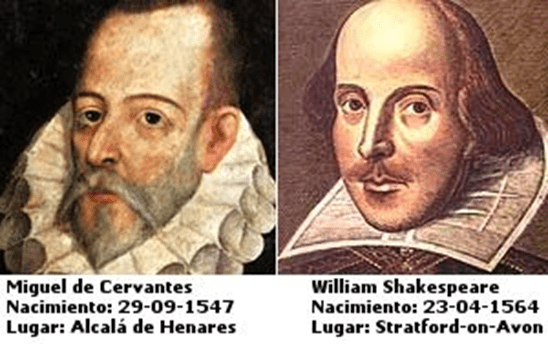

Another example is that England’s William Shakespeare and Spain’s Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote of La Mancha. They died on the same date, April 23, 1616, but when the differences between England’s Julian Calendar and Spain’s Gregorian Calendar are removed, Cervantes actually died ten days before Shakespeare.

In 1752, England and its colonies finally adopted the Gregorian Calendar, but by that time there was an 11 day discrepancy between the “Old Style” (OS) and the “New Style” (NS). When America finally adjusted its calendar, the day after September 2, 1752 (Old Style), became September 14, 1752 (New Style). There were reportedly accounts of confusion and rioting. As countries of Western Europe, particularly Portuguese, Spanish, French, Dutch and English, began to trade and establish colonies around the world, the Gregorian Calendar came into international use around the globe.

All dates in the world are either BC “Before Christ” or AD “Anno Domini” — meaning in the Year of the Lord’s Reign.

(So as confusing as all that appears, it is how we got to today’s calendar.)

Ron