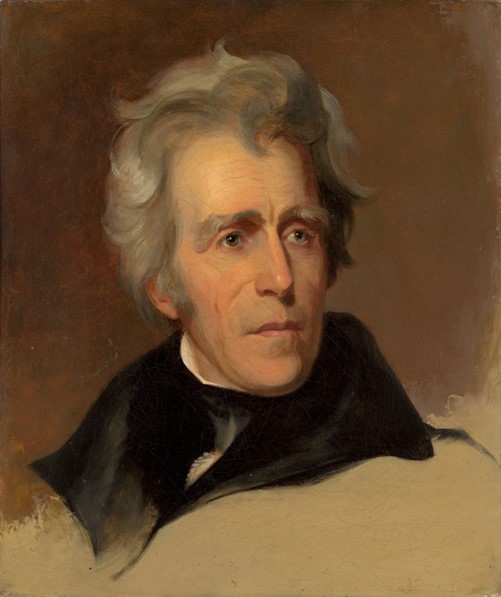

Old Hickory

Most folks know that Andrew Jackson’s picture is on our $20 dollar bill, that he won the Battle of New Orleans, that he was the 7th president of the United States, and that he was considered rough and rowdy in Washington, but little else about him. I hope you will read the following, and learn what an amazing man that he really was. And how useful it would be to have a man like him back there again today!

Ron

Beginning in 1606, England’s King James I transplanted large numbers of Presbyterians from Scotland into Ulster, a province in Northern Ireland. They were mostly tenant farmers who grew flax for the linen industry and grazed sheep for the wool industry.

In the first half of the 1700s, Ulster farmers suffered from rising rents and a famine. This led to a great Ulster migration of over 250,000 Scots-Irish Protestants to America.

One of these families was the Jackson family. Andrew Jackson’s Scots-Irish parents emigrated to America two years before his birth, March 15, 1767. A month before he was born, his father died in a log-hauling accident in Waxhaw hills of North Carolina.

At age 13, Andrew Jackson joined a local militia to fight during the Revolutionary War.

His eldest brother, Hugh Jackson, died during the Battle of Stono Ferry, June 20, 1779.

Andrew and another brother, Robert, were taken prisoner and nearly starved to death. Robert contracted smallpox in prison and died.

A British officer ordered young Andrew Jackson to polish his boots.

When Andrew refused, the officer drew his sword and slashed him across the head, arm and hand, leaving Andrew with permanent scars.

On May 29, 1780, British forces, numbering 14,000, laid siege to Charleston, South Carolina. After six weeks, American Major General Benjamin Lincoln surrendered. Nearly 6,000 Americans were taken captive, the largest number of Americans taken captive prior to the Civil War. Buildings were converted into prisons, and many prisoners were put on British starving ships where they contracted diseases.

Andrew Jackson’s mother, Elizabeth, along with other women, volunteered to care for the sick American prisoners. Tragically, Elizabeth Jackson contracted “ship fever” and died, being buried in an unmarked grave.

Andrew Jackson was an orphan at age 14.

Jackson supported and educated himself, eventually becoming a frontier country lawyer. In 1788, at the age of 21, was appointed prosecutor of the Western District.

In 1796, at the age of 29, Jackson was elected as a delegate to the Tennessee constitutional convention, where he is credited with proposing the Indian name “Tennessee.”

Tennessee citizens elected Jackson a U.S. Congressman, then U.S. Senator.

In 1798, Jackson served as a judge on Tennessee’s Supreme Court.

Speculating in land, Jackson bought the Hermitage plantation near Nashville and was one of three investors who founded Memphis.

Conflicts with Indians increased, being incited by the British.

The New Madrid Earthquake temporarily reversed the flow of the Mississippi River and the Great Comet of 1811 helped convince Indians to back Shawnee Chief Tecumseh, whose name meant “shooting star.”

Indians were armed by the British during the War of 1812.

British backed Red Stick Creek Indians massacred 500 Americans at Fort Mims, Alabama.

Andrew Jackson was sent to fight the British-backed Red Stick Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. One of Jackson’s soldiers was the young Sam Houston, who was wounded, but kept fighting. Another soldier was Davy Crockett, who later became a Tennessee Congressman. Davy Crockett and Sam Houston helped Texas gain independence from Mexico. (These were the kinds’ of men who were attracted to “Old Hickory”.)

During the War of 1812, at the Battle of Tallasehatchee, a dead Creek woman was found clutching her living baby. The other Indian women refused to care for the infant boy, so Jackson brought him home and raised him as his son, naming him Lincoyer.

Andrew Jackson drove the British out of Pensacola, November 9, 1814, then left the city in the control of the Spanish.

He went on to defend Mobile, Alabama, then New Orleans, Louisiana.

A strict battlefield officer, Jackson was described as being “tough as old hickory,” leading to his nickname “Old Hickory.”

Against overwhelming odds, Andrew Jackson defeated 10,000 British at the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815. Aided by Jean Lafitte’s French pirates, along with Kentucky and Tennessee sharpshooters, over 2,000 British were killed or wounded, as compared to only 71 American casualties.

Considered the greatest American land victory of the war, General Andrew Jackson wrote to Robert Hays, January 26, 1815: “It appears that the unerring hand of Providence shielded my men from the shower of balls, bombs, and rockets, when every ball and bomb from our guns carried with them a mission of death.”

{Now be patient with me, and let me stop and give you a detailed description of this famous Battle of New Orleans:}

In December 1814, even as diplomats met in Europe to hammer out a truce in the War of 1812, British forces mobilized for what they hoped would be the campaign’s finishing blow. Following military victories against Napoleon in Europe earlier that year, Great Britain had redoubled its efforts against its former colonies and launched a three-pronged invasion of the United States.

American forces had managed to check two of the incursions at the Battle of Baltimore (the inspiration for Francis Scott Key’s “Star-Spangled Banner”) and the Battle of Plattsburgh, but now the British planned to invade New Orleans, a vital seaport and the gateway to the United States’ newly purchased territory in the West, procured through the Louisiana Purchase.

If it could seize the Crescent City, the British Empire would gain dominion over the Mississippi River and hold the trade of the entire American South and the West under its thumb.

Standing in the way of the British advance was Major General Andrew Jackson, who had rushed to New Orleans’ defense when he learned an attack by the British was in the works. Nicknamed “Old Hickory” for his legendary toughness, Jackson had spent the last year subduing hostile Creek Indians in Alabama and harassing the redcoats’ operations along the Gulf Coast.

The General had no love for the British, he had spent time as their prisoner during the Revolutionary War, and he was itching for a chance to confront them in battle. “I owe to Britain a debt of retaliatory vengeance,” he once told his wife, “should our forces meet I trust I shall pay the debt.”

After British forces were sighted near Lake Borgne, Jackson declared martial law in New Orleans and ordered that every available weapon and able-bodied man be brought to bear in the city’s defense. His force soon grew into a 4,500-strong patchwork of army regulars, frontier militiamen, free blacks, New Orleans aristocrats and Choctaw tribesmen. The frontier men from Alabama and Tennessee with their long, accurate rifles and their wild lust for action were formidable foes.

After some hesitation, Old Hickory even accepted the help of Jean Lafitte, a dashing pirate who ran a smuggling and privateering empire out of nearby Barataria Bay.

The two sides first came to blows on December 23, when Jackson launched a daring nighttime attack on British forces bivouacked nine miles south of New Orleans. Jackson then fell back to Rodriguez Canal, a ten-foot-wide millrace located near Chalmette Plantation off the Mississippi River.

Using the labor of all those available, he widened the canal into a defensive trench and used the excess dirt to build a seven-foot-tall earthen rampart buttressed with timber. When completed, this “Line Jackson” stretched nearly a mile from the east bank of the Mississippi to a nearly impassable marsh or swamp filled with cypress trees.

Jackson’s ramshackle army was to face off against some 8,000 British regulars, many of whom had served in the Napoleonic Wars, hardened real soldiers of those days.

At the helm was Lieutenant General Sir Edward Pakenham, a respected veteran of the Peninsular War and the brother-in-law of the Duke of Wellington.

The two sides first came to blows on December 23, when Jackson launched a daring nighttime attack on British forces bivouacked nine miles south of New Orleans. Jackson then fell back to Rodriguez Canal, a ten-foot-wide millrace located near Chalmette Plantation off the Mississippi River.

Using all available labor, he widened the canal into a defensive trench and used the excess dirt to build a seven-foot-tall earthen rampart buttressed with timber and cotton bales. When complete, this “Line Jackson” stretched nearly a mile from the east bank of the Mississippi to a nearly impassable marsh or swamp filled with cypress trees.

“Here we shall plant our stakes,” Jackson told his men, “and not abandon them until we drive these red-coat rascals into the river, or the swamp.”

Despite their imposing fortifications, Lieutenant General Pakenham believed the “dirty shirts,” as the British called the Americans, would wilt before the might of a British army in formation. Following a skirmish on December 28 and a massive artillery duel on New Year’s Day, he devised a strategy for a two-part frontal assault.

A small force was charged with crossing to the west bank of the Mississippi and seizing an American battery. Once in possession of the guns, they were to turn them on the Americans and catch Jackson in a punishing crossfire. At the same time, a larger contingent of some 5,000 men would charge forward in two columns and crush the main American line at the Rodriguez Canal.

Pakenham put his plan to action at daybreak on January 8. At the sound of a Congreve rocket whistling overhead, the red-coated throngs let out a cheer and began an advance toward the American line. British batteries opened up en masse, and were immediately met with an angry barrage from Jackson’s 24 artillery pieces, some of them manned by Jean Lafitte’s pirates.

While Pakenham’s main force moved on the canal near the swamp, British light troops led by Colonel Robert Rennie advanced along the riverbank and overwhelmed an isolated redoubt, scattering its American defenders.

Rennie had just enough time to howl, “Hurrah, boys, the day is ours!” before he was shot dead by a salvo of rifle fire from Line Jackson. With their commander lost, his men made a frantic retreat, only to be cut down in a hail of musket balls and grapeshot (small caliber round shot packed inside canvas).

Pakenham had counted on moving under the cover of morning mist, but the fog had risen with the sun, giving American rifle and artillerymen clear sightlines. Cannon fire soon began slashing gaping holes in the British line, sending men and equipment flying.

General Pakenham

As the British troops continued the advance, their ranks were riddled with musket shot. General Jackson watched the destruction from a perch near the right side of the line, bellowing, “Give it to them, my boys! Let us finish the business today!” Old Hickory’s militiamen, having honed their aim hunting in the woods of the frontier, fired with terrifying precision.

Red-coated soldiers fell in waves with each American volley, many with multiple wounds. One stunned British officer later described the American rampart as resembling “a row of fiery furnaces.”

Pakenham’s plan was quickly unraveling. His men had bravely stood their ground amid the chaos of the American deluge, but a unit carrying ladders needed to scale Line Jackson was lagging behind. Pakenham took it upon himself to lead the outfit to the front, but in the meantime, his main formation was cut to ribbons by rifle and cannon fire.

When some of the redcoats began to flee, one of Pakenham’s subordinates unwisely tried to wheel the 93rd Highlanders Regiment to their aid. American troops quickly took aim and unleashed a maelstrom of fire that felled more than half the unit, including its leader. Around that same time, Pakenham and his entourage were laced by a blast of grapeshot. The British commander perished minutes later.

At Line Jackson, the British were retreating in droves, leaving behind a huge carpet of crumpled bodies. American Major Howell Tatum later said the enemy casualties were “truly distressing. Some had their heads shot off, some their legs, some their arms. Some were laughing, some crying. There was every variety of sight and sound.”

The assault on Jackson’s fortifications was a fiasco, costing the British some 2,000 casualties, including three generals and seven colonels all of it in the span of only 30 minutes. Amazingly, Jackson’s ragtag outfit had lost fewer than 71 men. Future President James Monroe would later praise the General by saying, “History records no example of so glorious a victory obtained with so little bloodshed on the part of the victorious.” The stunned British army lingered in Louisiana for the next several days, but its remaining officers knew that any chance of taking the Crescent City had slipped through their fingers. The British boarded their ships and sailed back into the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1817, President Monroe charged Jackson with stopping Seminoles in Florida from raiding into Georgia, resulting in the First Seminole War.

With Spain exhausted after Napoleon’s invasion, and with Mexico fighting for Independence, the Spanish government agreed to cede Florida to the U.S. in 1819 in exchange for payment, according to John Quincy Adams’ Adams-Onís Treaty.

This led to Jackson serving as Florida’s first territorial governor. The city of Jacksonville is named for him.

Circuit-riding preacher Peter Cartwright wrote of meeting Jackson, as recorded in the Autobiography of Peter Cartwright the Backwoods Preacher (pp. 192-194): “I then read my text: ‘What shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his own soul?’

After reading my text I paused. At that moment I saw General Jackson walking up the aisle; he came to the middle post, and very gracefully leaned against it, and stood, as there were no vacant seats.

Just then I felt someone pull my coat in the stand, and turning my head, my fastidious preacher whispering a little loud, said: ‘General Jackson has come in; General Jackson has come in.’

I felt a flash of indignation run all over me like an electric shock, and facing about to my congregation, and purposely speaking out audibly, I said, ‘Who is General Jackson? If he don’t get his soul converted, God will damn him as quick as he would anyone.’

Shortly after I met the General on the pavement; and before I approached him by several steps he smiled and reached out his hand and said:

‘Mr. Cartwright, you are a man after my own heart. I am very much surprised at Mr. Mac, to think he would suppose that I would be offended at you. No, sir; I told him that I highly approved of your independence; that a minister of Jesus Christ ought to love everybody and fear no mortal man.

I told Mr. Mac that if I had a few thousand such independent, fearless officers as you were, and a well-drilled army, I could take old England.”

Peter Cartwright continued: “General Jackson was certainly a very extraordinary man. He always showed a great respect for the Christian religion, and the feelings of religious people, especially ministers of the Gospel. I will here relate a little incident that shows his respect for religion.

I had preached one Sabbath near the Hermitage, and, in company with several gentlemen and ladies, went, by special invitation, to dine with the General. Among this company here was a young sprig of a lawyer from Nashville, of very ordinary intellect, and he was trying hard to make an infidel of himself. As I was the only preacher present, this young lawyer kept pushing his conversation on me, in order to get into an argument. I tried to evade an argument. This seemed to inspire the young man with more confidence.

I saw General Jackson’s eye strike fire, as he sat by and heard the thrusts he made at Christian religion. At length the young lawyer asked me this question: ‘Mr. Cartwright, do you really believe there is any such place as hell, as a place of torment?’ I answered promptly, ‘Yes, I do.’

To which he responded, ‘Well, I thank God I have too much sense to believe any such thing.’ I was pondering in my own mind whether I would answer him or not, when General Jackson for the first time broke into the conversation, and directing his words to the young man, said with great earnestness: ‘Well, sir, I thank God that there is such a place of torment as hell.’ This sudden answer made with great earnestness seemed to astonish the youngster, and he exclaimed: ‘Why, General Jackson, what do you want with such a place of torment as hell?’ To which the General replied, as quick as lightning, ‘To put such d—–d rascals as you are in, that oppose and vilify the Christian religion. ‘The young lawyer was struck dumb, and presently was found missing.’”

Jackson’s wife, Rachel, was divorced and abandoned by her first husband, but she was unaware that he had failed to file the paperwork, leaving her still legally bound when she met and married Jackson.

Jackson defended his wife’s honor, even challenging slanderers to duel him.

His many duels left him with so many bullet fragments in his body, that they said he “rattled like a bag of marbles” when he walked.

Jackson described his wife as the most pious person he ever knew.

He wrote to her, December 21, 1823: “I trust that the God of Isaac and of Jacob will protect you, and give you health in my absence, in Him alone we ought to trust, He alone can preserve, and guide us through this troublesome world, and I am sure He will hear your prayers. We are told that the prayers of the righteous prevaileth much, and I add mine for your health and preservation until we meet again.”

During his Presidential campaign, the vicious personal attacks on his wife brought her so much stress that she suffered a stroke and died.

Her last words before collapsing were: “I’d rather be a doorkeeper in the house of God than to live in that palace in Washington.”

Rachel was buried Christmas Eve,1828, on the Hermitage estate, dressed in the inaugural gown she would have worn in Washington. Weeping profusely, Jackson said: “I know it’s unmanly, but these tears are due her virtues. She has shed many for me. In the presence of this dear saint, I can and do forgive my enemies. But those vile wretches who have slandered her must look to God for mercy.”

Jackson stated: “Heaven will be no heaven to me if I do not meet my wife there.”

Three months later, Jackson was sworn in as the 7th President, March 4, 1829. In his 2nd Inaugural Address, Andrew Jackson stated: “It is my fervent prayer to that Almighty Being before whom I now stand, and who has kept us in His hands from the infancy of our Republic to the present day, that He will inspire the hearts of my fellow-citizens that we may be preserved from danger.”

Andrew Jackson, as President, made negative and positive decisions,

yet he paid off the national debt the only President to do so,

and curtailed the power of globalist-type bankers in The Bank War.

The Bank War began when Nicholas Biddle sought to have his Second Bank of the United States gain monopoly control over the nation’s financial system.

Twenty percent of the bank was owned by foreign investors.

Andrew Jackson withdrew Federal funds out of the Second Bank of the United States and vetoed a renewal of its charter, stating in 1832:

“Controlling our currency, receiving our public moneys, and holding thousands of our citizens in dependence, it would be more … dangerous than the naval and military power of the enemy.”

He continued: “Some of the powers possessed by the existing bank are unauthorized by the Constitution, subversive of the rights of the States, and dangerous to the liberties of the people.”

Andrew Jackson told his Vice-President Martin Van Buren: “The bank, Mr. Van Buren, is trying to kill me, but I will kill it.”

Jackson stated December 5, 1836: “The experience of other nations admonished us to hasten the extinguishment of the public debt …

An improvident (shortsighted) expenditure of money is the parent of profligacy corruption. No people can hope to perpetuate their liberties who long acquiesce in a policy which taxes them for objects not necessary to the legitimate and real wants of their Government.”

He continued: “To require the people to pay taxes to the Government merely that they may be paid back again nothing could be gained by it even if each individual who contributed a portion of the tax could receive back promptly the same portion.”

He added: “Congress is only authorized to levy taxes ‘to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.’

There is no such provision as would authorize Congress to collect together the property of the country, under the name of revenue, for the purpose of dividing it equally or unequally among the states or the people.

Indeed, it is not probable that such an idea ever occurred to the states when they adopted the Constitution. There would soon be but one taxing power, and that vested in a body of men far removed from the people, in which the farming and mechanic interests would scarcely be represented”

Jackson ended: “The states would gradually lose their purity as well as their independence; they would not dare to murmur at the proceedings of the General Government, lest they should lose their supplies; all would be merged in a practical consolidation, cemented by widespread corruption, which could only be eradicated by one of those bloody revolutions which occasionally overthrow the despotic systems of the Old World.”

(These thoughts shown above about the Bank War were composed by liberal professors of history and are accurate, but not how I would describe the “Bank War”. I would say that when Andrew Jackson encountered what we call today “The Deep State” in Washington and that were mostly composed of bankers, he just cleaned out the whole mess. Really, we need him back today for the same purpose.)

On May 6, 1833, Jackson was on his way to lay the cornerstone for the monument to George Washington’s mother, Mary Ball Washington.

Stopping at Alexandria, Virginia, Robert Randolph came up and struck the President, then ran away. He was chased down by those accompanying the President, including writer Washington Irving, but Jackson refused to press charges.

Then, on January 30, 1835, following a funeral in Washington, Richard Lawrence approached Jackson and fired two pistols at him at point blank range, but both misfired, possibly due to a fog dampening the gunpowder.

Davy Crockett wrestled the assailant down.

Senator Thomas Hart Benton wrote how the incident: “irresistibly carried many minds to the belief in a superintending Providence, manifested in the extraordinary case of two pistols in succession so well loaded, so cooly handled, and which afterwards fired with such readiness, force, and precision missing fire each in his turn, when leveled eight feet at the President’s heart.”

King William the Fourth of England heard of the incident and expressed his concern. President Jackson wrote back, exclaiming: “A kind Providence had been pleased to shield me against the recent attempt upon my life, and irresistibly carried many minds to the belief in a superintending Providence.”

Since Andrew Jackson’s wife had died before he took office, his nephew’s wife, Emily Donelson, served as the unofficial First Lady. When Emily Donelson died suddenly, President Jackson wrote to her husband, Colonel Andrew Jackson Donelson, December 30, 1836: “We cannot recall her, we are commanded by our dear Savior, not to mourn for the dead, but for the living. She has changed a world of woe for a world of eternal happiness, and we ought to prepare as we too must follow. ‘The Lord’s will be done on earth as it is in heaven.'”

On March 25, 1835, Andrew Jackson wrote in a letter to Ellen Hanson:

“I was brought up a rigid Presbyterian, to which I have always adhered.

Our excellent Constitution guarantees to everyone freedom of religion, and charity tells us and you know Charity is the real basis of all true religion — and charity says judge the tree by its fruit. All who profess Christianity believe in a Savior, and that by and through Him we must be saved.”

Jackson concluded: “We ought, therefore, to consider all good Christians whose walks correspond with their professions, be they Presbyterian, Episcopalian, Baptist, Methodist or Roman Catholic.”

On JUNE 8, 1845, “Old Hickory” died.

Jackson had stated, referring to the Bible: “That book, Sir, is the Rock upon which our republic rests.”

During the War of 1812, General Andrew Jackson penned his 2nd Division Orders, March 7, 1812: “Who are we? And for what are we going to fight?

Are we the titled slaves of George the third? The military conscripts of Napoleon the great? Or the frozen peasants of the Russian Czar?

No, we are the free born sons of America; the citizens of the only republic now existing in the world; and the only people on Earth who possess rights, liberties, and property which they dare call their own.”