The liberals in the United States have been on a crusade to erase our great Christian men of history from the record. Since his life was obviously directed by God, Christopher Columbus is one of those they seem determined to erase. One of our holidays was Columbus Day. They don’t want that any more, and don’t want his exploits taught in our schools. You may have trouble finding anything accurate about him now. Thus, I have sent this short compilation of some of his deeds to you.

Ron

Mehmet II succeeded his father, Murad II, to rule the Muslim Ottoman Empire.

After killing his brothers, he later formalized this practice into law, stating:

“Whichever of my sons inherits the sultan’s throne, it behooves him to kill his brothers in the interest of the world order.”

Mehmet II

On May 29, 1453, at the age of 21, Mehmet II conquered the Byzantine city of Constantinople, the largest and richest city in Europe.

Located on the Bosporus, where the East and West met, it largely served as the capital of Christendom for over a thousand years.

Mehmet had stated: “The ghaza (holy war) is our basic duty, as it was in the case of our fathers. The conquest of (Constantinople) is essential to the future and the Ottoman state.”

Mehmet II Conquers Constantinople

Even socialist historian Howard Zinn admitted in A People’s History of the United States (1980): “Now that the Turks had conquered Constantinople and the eastern Mediterranean, and controlled the land routes to Asia, a sea route was need and Spain decided to gamble on a long sail across an unknown ocean.”

William Lawson Grant, Professor of Colonial History at Queens University, Kingston, Ontario, wrote in the introduction to Voyages and Explorations (Toronto, The Courier Press, Limited, 1911, A.S. Barnes Company): “The history of Western Civilization begins in a conflict with the Orient, a conflict of which it may be the end is not yet.

The routes between East and West have been trodden by the caravans of trade more often even than by the feet of armies.

The treasures of the East were long brought overland to Alexandria, or Constantinople, or the cities of the Levant, and thence distributed to Europe by the galleys of Genoa or of Venice.

But when the Turk placed himself astride the Bosporus, and made Egypt his feudatory, new routes had to be found.”

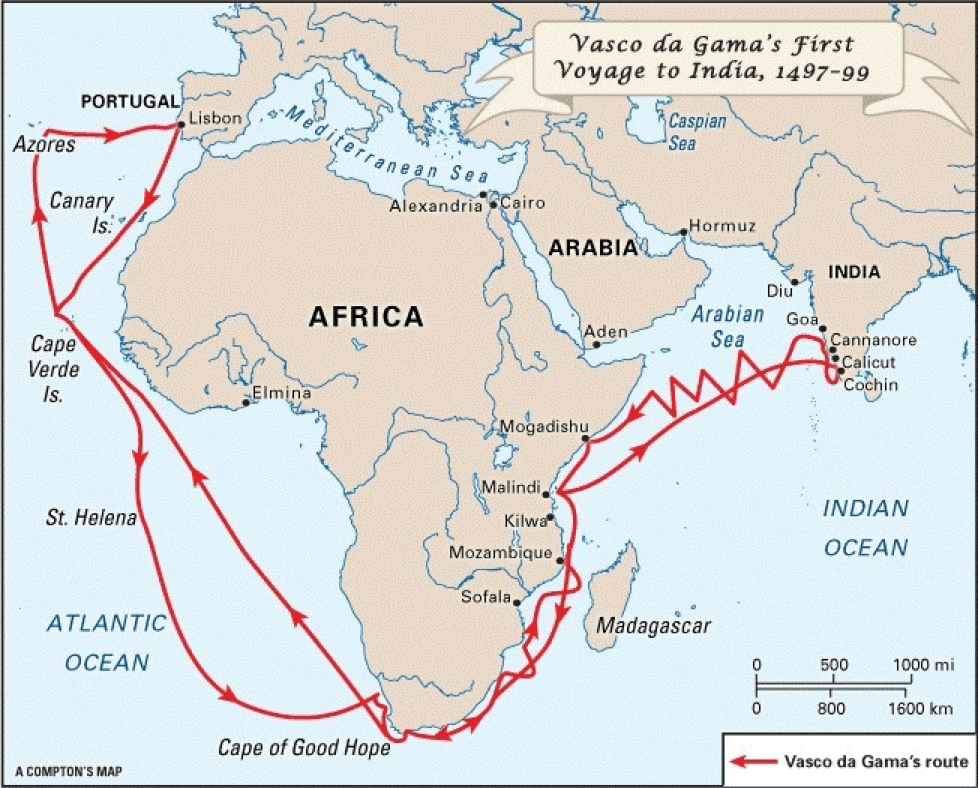

Grant continued in Voyages and Explorations: “In the search for these were made the three greatest voyages in history, those

of Columbus,

of Vasco da Gama, and

greatest of all of Magellan …

In his search for the riches of Cipangu (Japan), Columbus stumbled upon America.

The great Genoese lived and died under the illusion that he had reached the outmost verge of Asia.”

In 1498, Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama successfully sailed around South Africa to India.

But six years earlier, Columbus proposed another westward SEA route.

1ST VOYAGE (1492-1493) was truly historic.

Columbus used his knowledge of the “trade winds” to make the longest voyage ever out of the sight of land.

Thinking he had made it to India, he referred to the inhabitants as “Indians,” and the name stuck.

It is interesting to consider that native Americans might never have been called “Indians” had it not been for Islamic jihad cutting off the land trade routes to India.

These first inhabitants were peaceful Taino Arawak natives.

Columbus thought that Cuba was the tip of China and that Hispaniola (Dominican Republican/Haiti) was Japan.

Returning to Europe, Columbus’ ship, Santa Maria, hit a reef off the coast of Hispaniola and wrecked on December 24, 1492. He left 39 sailors in a make-shift fort named La Navidad.

2ND VOYAGE (1493-1496), Columbus was frustratingly saddled with 17 ships and 1,500 mostly get-rich-quick Spanish opportunists.

This was the doings of the jealous Spanish Bishop Juan Rodriguez de Fonseca, who continually undermined Columbus at the royal court. Fonseca thought it was a mistake that the Spanish Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, gave so much authority to a “non-Spaniard” — Columbus being just a low-class Genoese, from the rival Italian city-state of Genoa.

In this sense, Columbus was the victim of racial discrimination. Bishop Fonseca is to be blamed for altering Columbus’ goal from finding India and China to managing hundreds of ambitious settlers. Columbus was an amazingly gifted explorer, but unfortunately failed miserably as a governor.

Looking for a location for a settlement, Columbus explored Puerto Rico and Jamaica.

Arriving at La Navidad, Hispaniola, they were shocked to find that the sailors Columbus had left the previous year were all killed by natives.

Reality set in. Instead of finding a paradise, Spaniards were shocked to discover the existence of aggressive Carib natives. Caribs would land on an island inhabited by the peaceful Taino Arawak natives and proceed to emasculated, and cannibalized them.

Columbus had them establish the settlement of La Isabella on Hispaniola, but shortly after it was destroyed in a hurricane, a storm of unbelievable intensity which none of them had experienced before. They abandoned La Isabella and founded a new settlement named Santo Domingo, presumably in honor of Columbus’ father Domenico.

After the hurricane, followed by malaria, together with the fear of cannibals, the Spanish settlers began to feel Columbus misrepresented this new world “paradise.” They began to grow impatient at having to obey Columbus, who, after all, was not even Spanish, but rather an Italian of low birth from Genoa.

Columbus unfortunately yielded to their greedy demands and allowed them set up European-style feudal plantations, called “mayorazgos.” This tragically set a precedent for generations of mistreatment of native populations.

Columbus sailed back to Spain, leaving his two younger brothers Bartholomew and Diego (Giacomo) in charge of Santo Domingo.

3RD VOYAGE (1498-1500), Columbus sailed across the Atlantic further south, closer to the equator.

This brought him through a stretch of sea called “the horse latitudes” and “the doldrums,” where there is no wind for weeks at a time.

Parched in the windless heat of the blazing sun, Columbus prayed that if the winds returned, he would name the first land he saw after the Trinity.

When the winds finally picked up, Columbus named the first land he saw “Trinidad.” Columbus then set foot and planted the Spanish flag on the Paria Peninsula of present-day Venezuela, August 1, 1498, making him the first European to set foot on South America.

He explored the beautiful Orinoco River, speculating that it could be the outer regions of the Garden of Eden.

When Columbus arrived back at his settlement of Santo Domingo, he found that the greedy Spanish settlers had rebelled against his brothers, Bartholomew and Diego.

In despair, Columbus sent a letter to the King, pleading for help.

The plea was intercepted by the ambitious Bishop Fonseca, who convinced the King that, instead of sending help, he should replace Columbus as governor.

The King sent a replacement governor named Bobakillo in 1515. Bobadillo arrested Columbus and his brother, and sent them back to Spain in chains.

Columbus wrote to a friend and confidante of the Queen, Dona Juana de Torres: “I undertook a new voyage to the New World which hitherto had been hidden. They judged me there as a governor who had gone to Sicily or to a city or town under a regular government. I should be judged as a captain who went from Spain to the Indies.”

4TH VOYAGE (1502-1504).

After a two year delay, Ferdinand and Isabella finally permitted Columbus to sail on May 12, 1502, from Cadiz, Spain, on his last voyage.

Columbus was forbidden to visit his settlement of Santo Domingo, but upon reaching the Caribbean, he was alarmed to see another hurricane brewing, similar to the one experienced at La Isabella.

Weighing the risk, he entered the harbor of Santo Domingo to warn them of the approaching danger and to seek shelter for his ships. He anchored and rowed ashore.

A second replacement governor had arrived named Orvando. He ignored Columbus. Orvando was preoccupied in preparing to send back to Spain the previous governor, Bobadillo, along with a treasure fleet of 30 ships filled with gold and native slaves.

Unwittingly, the ships would be heading directly into the path of the hurricane. Columbus’ warning was completely spurned, as he was considered an unwelcome persona-non-grata. Orvando ordered Columbus to immediately leave the harbor.

With the hurricane now fast approaching, Columbus did not even take the time to pull aboard his row boat. He sailed as fast as he could to seek shelter from the wind on the far side of the island.

The hurricane hit around July 1, 1502, with such fury that it almost completely destroyed Santo Domingo.

Of the treasure fleet, 4 ships returned to Santo Domingo, and 25 sank, with the loss of approximately 500 lives, including Bobadillo.

The one ship that survived and made it to Spain was the Aguja. It was so old and slow that it had not yet cleared the island mangroves when the hurricane hit.

When the ship arrived in Spain, to everyone’s amazement, it was found to be the one carrying Columbus’ portion of the gold, per his initial agreement with Ferdinand and Isabella.

The providential nature of this incident vindicated Columbus’ reputation, though he did not find out about it for over a year, as he was blown around the Caribbean.

Describing the violent weather, Columbus recorded: “The tempest arose and wearied me so that I knew not where to turn, my old wound opened up, and for 9 days I was lost without hope of life; eyes never beheld the sea so angry and covered with foam.”

He continued:

“The wind not only prevented our progress, but offered no opportunity to run behind any headland for shelter; hence we were forced to keep out in this bloody ocean, seething like a pot on a hot fire. The people were so worn out that they longed for death.”

After a day and a half of continuous lightning, Columbus’ 15-year-old son, Ferdinand, recorded that on December 13, 1502, a waterspout passed between the ships: “the which had they not dissolved by reciting the Gospel according to St. John, it would have swamped whatever it struck for it draws water up to the clouds in a column thicker than a waterbutt, twisting it about like a whirlwind.”

Columbus’ biographer, Samuel Eliot Morrison described Admiral Columbus: “It was the Admiral who exorcised the waterspout. From his Bible he read of that famous tempest off Capernaum, concluding, ‘Fear not, it is I!’ Then clasping the Bible in his left hand, with drawn sword he traced a cross in the sky and a circle around his whole fleet and they were miraculously saved.”

Columbus explored the coasts of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica.

He briefly landed in Panama, but was too ill and too suspicious of the natives to cross the 50 mile-wide isthmus on foot to the Pacific side, where he could have seen the real route to India and China.

As it was, they were attacked by Indians, and barely made it out of a shallow Belen River at low tide with 3 of his 4 ships. Another ship was lost in a storm off Cuba.

With his last two ships worm-eaten and taking on water, he beached them on the Island of Jamaica at St. Anne’s Bay, on June 25, 1503, marooned for the next year.

Natives at first accommodated them, but the situation deteriorated when some sailors began an unruly mutiny.

Fearing an attack, Columbus had to act fast. An accomplished explorer, Columbus had been diligent to keep track of the position of the moon and stars in the night sky of the Western Hemisphere, something that had never been observed before.

Using astronomic tables made by Rabbi Abraham Zacuto of Spain, Columbus summoned the chiefs to his marooned ships on the specific night of February 29, 1504. When he correctly predicted a lunar eclipse, the natives became afraid and convinced Columbus had divine favor.

They abandoned their plans of attack and continued to provide for them.

Finally, Columbus’ captain, Diego Méndez de Segura, purchased a canoe from the natives and set off with several of them from Jamaica toward Hispaniola (Haiti), crossing 450 miles of open sea.

Arriving there, Méndez found Governor Ovando in the jungle, subduing the Taino Arawak natives.

Ovando was not thrilled to hear that Columbus was still alive and waited months to send help.

Being rescued at last he then finished his exploration of the coast of Panama. Columbus anchored the fleet on 6 January 1503 at the mouth of a river he named Belen. He decided to remain in the area at least until the end of the rainy season, and sent patrols to search for gold. Upon discovering entire “mines of gold,” the Admiral decided to establish a settlement at Belen; Christopher would leave his brother, Bartholomew, in charge while he returned to Spain.

The men set out in February to establish the settlement on the river shore, but their efforts were soon interrupted by aggressive natives, who hoped to kill the intruders.

On 6 April, the day that Christopher was to sail for Spain, the majority of his party accompanied the Admiral to his ships to bid farewell, leaving only 20 men and a dog on the shore. With a large numerical advantage, 400 heavily armed natives descended on the small guard party, killing one and wounding several, including Bartholomew.

In the meantime, ignorant of the attack, Columbus sent a group of men ashore to take on a final load of water for the return voyage. The men of this party walked right into the Indians’ hands, and all but one of this company were killed.

During the fight, the Admiral was left alone aboard his ship, the Capitana, which was anchored about a mile off shore. Physically sick and, no doubt, greatly distressed over the plight of his men, Columbus climbed to the top of the vessel and tried desperately to attract the attention of his war captains. After calling, unsuccessfully, for his men, he eventually succumbed to exhaustion and fell asleep.

Slumbering aboard the Capitana, Christopher had perhaps the most remarkable, and sobering, spiritual experience of his life. He “heard a compassionate voice,” calling him to repentance:

“O fool, and slow to believe and serve thy God, the God of every Man! What more did He do for Moses or for David His servant than for thee? From thy birth He hath ever held thee in special charge. When He saw thee at man’s estate, marvelously did He cause thy name to resound over the earth. The Indies, so rich a portion of the world, He gave thee for thine own, and thou hast divided them as it pleased thee. Of those barriers of the Ocean Sea, which were closed with such mighty chains, He hath given thee the keys. Thou hast won noble fame from Christendom. Turn thou to Him and acknowledge thy faults; His mercy is infinite.”

This incident was, in fact, a moving call to repentance for the Admiral. The records of his earlier life make clear that Christopher had a keen spiritual sense about him; his expressions of faith and gratitude to the Lord were both impressive and numerous.

With these poignant thoughts to ponder, the Admiral returned to Spain in November 1504 to live out the last year-and-a-half of his illustrious, yet turbulent, life. He died in Valladolid, Castile, on Wednesday, 20 May 1506, but wrote out his last words: “‘in manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum’ (‘into your hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit’)”

Though unsuccessful as a governor, Columbus was nevertheless one of the world’s most accomplished sailors and explorers, and though he did not reach India or China, he did change history, and was totally devoted to God.